Is there a point where Buddhism and artificial intelligence could converge? Yes, there are already some perspectives on how a religion so grounded in the human conscious experience would regard a hypothetical sentient machine; one can only wonder how such an alien intelligence would itself consider introspective practices created by and for our own organic minds. A more practical starting point might be using machine learning to help us understand Buddhism, especially those of us in parts of the world to which it has only been introduced within the past few generations. There are many good high-level introductory resources, but more serious students must navigate a massive amount of scripture and philosophy, full of terms and concepts that are notoriously difficult to translate well into Western languages, without the benefit of a long-term cultural context.

In this post, I’m implementing the word2vec architecture with Tensorflow and using it to learn word embeddings for a large subset of the Pāli Canon, the oldest collection of Buddhist scriptures. I’ll show results comparable to the original implementation, and along the way will highlight some interesting structure that emerges from the text.

The Pāli Canon

The Pāli Canon is the portrayal of Buddhist philosophy closest to the original teachings of Gautama Buddha, who lived between the 4th and 6th centuries BCE. After generations of oral transmission by monks, it was committed to writing in the Pāli language in 29 BCE, complete with its distinctively lyrical, repetitive style that made it ideal for memorization and chanting. In addition to elucidating the foundations of Buddhist thought, text in the Pāli Canon reveals insights into a wide cross section of life in India at the end of the Vedic period, a time of significant social, political, philosophical and religious change.

Specifically, I am examing one the three divisions of the Pāli Canon called the Sutta Pitaka. The Sutta Pitaka is a collection of suttas (or sutras), which are typically discourses, poetry and other short writings. They are usually delivered by the Buddha himself and include sermons, instructions and training for monks, debates with other religious thinkers of the era, and conversations with a whole galaxy of people, from homeless wanderers to kings and celestial beings.

Though only a portion of the Canon, the Sutta Pitaka is of significant length, with authoritative English translations of just four of the five books coming to over 6,000 pages. There is no chronological ordering of suttas between or within books, so systematic study requires some expert guidance to sequence. Only a loose grouping by theme or intended audience can be found in some places.

A large subset of the Sutta Pitaka is available from Access to Insight (ATI), an online archive of Theravada Buddhism, which conveniently provides a whole-website download.

Word Embeddings

The machine learning model used here is an implementation of word2vec. Word2vec generates word embeddings, which map words to feature vectors such that words appearing in similar contexts are close neighbors in the vector space. Before word embeddings were widely used, features for words in natural language processing (NLP) typically had much higher dimensionality: one feature per word for many thousands or tens of thousands of words, as opposed to a denser vector space of a few hundred dimensions. Per-word features were often extremely sparse and were lost important contextual information that word embeddings preserve. Although introduced over a decade ago, recent improvements in quality and training speed have recently made them one of the most powerful NLP tools in use today.

Word embeddings are often learned for use as features in other learning algorithms but have some interesting properties that make them useful on their own. Analysis of a word vector’s nearest neighbors can reveal information about the structure and content of a corpus, and the spatial qualities of that structure can mirror real linguistic and conceptual relationships. For example, one of the word2vec papers demonstrates that simple algebraic operations on embeddings can represent analogies: the vector king - man + woman is very close to the vector for queen.

The C implementation of Word2vec provides hyperparameters for feature generation and learning. Features are generated using either a continuous bag-of-words (CBOW) or skip-gram model. These can be understood as inverses of each other: in CBOW, words within a context window predict a target word, whereas skip-grams predict context words from a target.

Word2vec is also computationally efficient. Instead of computing probabilities for every word in the vocabulary at every training step, it uses one of several techniques for sampling. This significantly reduces what would otherwise be a prohibitively long and resource-intensive training process in many cases.

Text Processing

I extracted sentences from 859 sutta translations from the ATI archive. Each was first parsed from HTML using Beautiful Soup, then processed by a series of regexes and filters. Overall the data set has a few unique features:

- Many words, including words for core concepts, are left untranslated from Pāli because accurate single or even multi-word translations for them in English are awkward or impossible. Additionally, many words like jhāna have accents applied inconsistently depending on the text and translator, and so all accented characters have been converted for consistency.

- Hyphenated words, like neither-perception-nor-nonperception are common, also because of difficulties in translation. These are preserved and considered single words.

- Some suttas, particularly those that are more well-known, have multiple different translations. Rather than pick and choose, I thought it was meaningful that they had additional representation and extracted text from each of them.

Below is a section of text from the Satipatthana Sutta after initial extraction. This sutta, which describes foundational practices for meditation, is one of the most well-known in the Canon.

The Blessed One said this: “This is the direct path for the purification of beings, for the overcoming of sorrow and lamentation, for the disappearance of pain and distress, for the attainment of the right method, and for the realization of Unbinding – in other words, the four frames of reference. Which four?

“There is the case where a monk remains focused on the body in and of itself – ardent, alert, and mindful – putting aside greed and distress with reference to the world. He remains focused on feelings… mind… mental qualities in and of themselves – ardent, alert, and mindful – putting aside greed and distress with reference to the world.

“And how does a monk remain focused on the body in and of itself?

“There is the case where a monk – having gone to the wilderness, to the shade of a tree, or to an empty building – sits down folding his legs crosswise, holding his body erect and setting mindfulness to the fore. Always mindful, he breathes in; mindful he breathes out.

Next, I tokenized each sutta into sentences and words using NLTK. Tokens were then stemmed to reduce noise in the vocabulary from plurals, possessives and other non-base forms of a word. There are many simple algorithms for stemming, but they have the unfortunate side effect of aggressively mutilating words into roots that are often not words themselves. Instead, I used NLTK’s WordNet stemmer, which lemmatizes words into base dictionary forms.

This requires part-of-speech tagging the text. Overall, results from the WordNet lemmatizer were significantly more legible than those from any other NLTK stemmer, at the cost of some accuracy, likely because of the injection of a large number of non-English words and some differences between the text and what the POS tagger had been trained on.

lemmatizer = nltk.stem.WordNetLemmatizer()

words = nltk.word_tokenize(sentence)

words = [w.lower() for w in words if len(w) > 0]

# pos tag + wordnet lemmatize

tagged = nltk.pos_tag(words)

tagged = [(t[0], convert_tag(t[1])) for t in tagged]

words = [lemmatizer.lemmatize(t[0], pos=t[1]) for t in tagged]

# remove any remaining artifacts

words = [w for w in words if len(w) > 1 or w in {'a', 'i', 'o'}]

words = [w for w in words if re.match(r'^[a-z/-]+$', w)]

Sentences were then written one line at a time to a single training file. The extracted text from the Satipatthana Sutta became:

the blessed one say this this be the direct path for the purification of being for the overcoming of sorrow and lamentation for the disappearance of pain and distress for the attainment of the right method and for the realization of unbind in other word the four frame of reference

which four

there be the case where a monk remain focus on the body in and of itself ardent alert and mindful put aside greed and distress with reference to the world

he remain focus on feeling mind mental quality in and of themselves ardent alert and mindful put aside greed and distress with reference to the world

and how do a monk remain focus on the body in and of itself

there be the case where a monk have go to the wilderness to the shade of a tree or to an empty building sit down fold his leg crosswise hold his body erect and set mindfulness to the fore

always mindful he breathe in mindful he breathe out

The data set contained 39,714 sentences, with 9368 unique and 707,528 total words.

Word Vector Model

My starting point was the Tensorflow tutorial for Vector Representations of Words. This tutorial introduces word embeddings, implements a basic word2vec architecture and applies it to a simplified version of the enwik8 corpus. At over 250 thousand unique and 17 million total words, it is also a significantly larger data set than the Pāli corpus. This particular version of the data set had already been preprocessed and reduced to one continuous stream of words without sentence or document breaks.

I first reformatted the Pāli text in the same way and ran it directly through the tutorial code. With no objective test data by which to measure the results, I evaluated them in two ways: by selecting a list of words for which I’d search for closest neighbors and judge their quality, and using the t-SNE visualizer from scikit-learn to generate a 2D projection of the vector space, where similar vectors would be grouped together on a plane.

Initially, the embeddings generated were good enough to be interesting, but only for very simple categorical associations, like colors and numbers. Unsure if this was as good as I could expect with a comparatively small dataset, I also ran a python wrapper for word2vec on the data set. The reference implementation produced vectors with significantly better neighbors, for both general words and categories as well as more Buddhism-specific concepts.

One obvious change was to alter feature extraction to generate skip-grams only within sentences. Words in a sentence are more likely to be related and contextually meaningful. Word2vec also filters out words occurring too infrequently in the text and provides a threshold parameter, below which words are completely removed from the corpus. This has the side effect of widening context windows, as it moves words into proximity that were more distant previously.

# count all words

for sentence in sentences:

self.counter.update(sentence)

# filter out words < threshold from vocabulary

top_words = [w for w in self.counter.most_common() if w[1] >= self.threshold]

self.counter = collections.Counter(dict(top_words))

# ids in descending order by frequency

self.dictionary = {c[0]: i for i, c in enumerate(self.counter.most_common())}

self.reverse_dictionary = dict(

zip(self.dictionary.values(), self.dictionary.keys()))

encoded = []

# encode word -> id, build vocabulary

for sentence in sentences:

selected = [w for w in sentence if w in self.counter]

encoded.append([self.dictionary[w] for w in selected])

self.vocabulary.update(selected)

self.total_words += len(selected)

self.sentences = encoded

Two sampling strategies are applied in word2vec when generating skip-grams. First, frequent words are aggressively downsampled, with an effect similar to filtering out stopwords (very common words like the, and, is, etc. that add little to no meaningful information to a sentence), but with the added benefits of not requiring a stopword list, and of subsampling words that aren’t stopwords but appear frequently anyway. This subsampling is also done before context windows are applied, further widening them.

Context windows are also dynamically adjusted, with the size at the time of skip-gram generation sampled between one and the input parameter for window size. This weights words that occur in close proximity more heavily than those at a distance, as they are more likely to fall within the sampled window.

selected = []

for word_id in sentence:

word = self.reverse_dictionary[word_id]

# subsample frequent words

frequency = self.counter[word] / self.total_words

sample_prob = (math.sqrt(frequency / self.sample) + 1) * (

self.sample / frequency)

if np.random.sample() > sample_prob:

continue

selected.append(word_id)

sentence = selected

skipgrams = []

for i, word_id in enumerate(selected):

# sample context window between 1 and window size

window = np.random.randint(low=1, high=self.window + 1)

start = max(i - window, 0)

end = min(i + window, len(selected) - 1)

# add all context words

for j in range(start, end + 1):

if j == i:

continue

skipgrams.append((word_id, selected[j]))

The Tensorflow model code used here is similar to that of the tutorial, with some modifications:

- I used a different loss function, sampled softmax instead of noise-contrastive estimation. This is largely due to observably better results and convergence with sampled softmax, which may be related to the comparatively small size of the dataset.

- I did not allow the loss function to use the default log uniform candidate sampler, instead opting for the learned unigram candidate sampler. Note that the default sampler assumes a Zipfian distribution in the input examples, which is effectively smoothed out by the subsampling during feature generation, so using it would be effectively double-subsampling the data. It’s also possible to remove subsampling entirely and rely on the candidate sampler; in practice, I found the approach used here yielded better results.

init = 1.0 / math.sqrt(self.embedding_size) # weight initialization

# input training examples & labels

self._train_examples = tf.placeholder(tf.int64, shape=[None], name='inputs')

self._train_labels = tf.placeholder(tf.int64, shape=[None, 1], name='labels')

# word vector embeddings

embeddings = tf.Variable(

tf.random_uniform([self.vocabulary_size, self.embedding_size], -init, init),

name='embeddings')

train_embeddings = tf.nn.embedding_lookup(embeddings, self._train_examples)

# softmax weights + bias

softmax_weights = tf.Variable(

tf.truncated_normal([self.vocabulary_size, self.embedding_size], stddev=init),

name='softmax_weights')

softmax_bias = tf.Variable(tf.zeros([self.vocabulary_size]), name='softmax_bias')

# don't use default log uniform sampler, distribution has been changed by subsampling

candidates, true_expected, sampled_expected = tf.nn.learned_unigram_candidate_sampler(

true_classes=self._train_labels,

num_true=1,

num_sampled=self.n_sampled,

unique=True,

range_max=self.vocabulary_size,

name='sampler')

# sampled softmax loss

self._loss = tf.reduce_mean(

tf.nn.sampled_softmax_loss(

weights=softmax_weights,

biases=softmax_bias,

labels=self._train_labels,

inputs=train_embeddings,

num_sampled=self.n_sampled,

num_classes=self.vocabulary_size,

sampled_values=(candidates, true_expected, sampled_expected)))

self._optimizer = tf.train.GradientDescentOptimizer(self.learning_rate).minimize(

self._loss)

self._loss_summary = tf.summary.scalar('loss', self._loss)

# inputs for nearest N

self._nearest_to = tf.placeholder(tf.int64)

# cosine similarity for nearest N

self._normalized_embeddings = tf.nn.l2_normalize(embeddings, 1)

target_embedding = tf.gather(self._normalized_embeddings, self._nearest_to)

self._distance = tf.matmul(

target_embedding, self._normalized_embeddings, transpose_b=True)

Exploring Nearest Neighbors

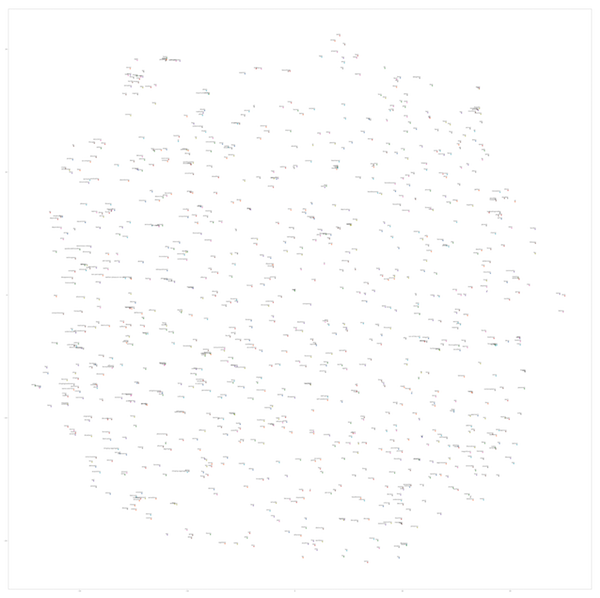

Below is a t-SNE plot of the most frequent 1000 words in the Pāli corpus. It’s very large, so click through the thumbnail for the full version.

The words in the first target set below have little to no specific meanings in Buddhism and are a check on the basic capabilities of the model. These words, including colors, numbers, body parts, familial relations and directions, are in most cases positioned close to other words that are within the same category or are have clear conceptual relationships.

north -> south, west, east, city, sky, countryside, gate, sol

skin -> tendon, teeth, nail, marrow, sweat, blood, flesh, grass

leg -> crosswise, fold, erect, shoulder, abash, rod, round, nail

blue -> yellow, red, white, feature, color, wild, lotus, skilled

five -> three, ten, nine, eleven, twenty, seven, four, eight

cow -> grass, dry, hillside, butcher, wet, bird, bathman, glen

day -> night, half, month, year, forward, spend, two, seven

mother -> father, child, brother, sister, wife, majesty, kinsman, relative

sword -> spear, cow, goat, knife, shield, bed, cover, garland

Next, the neighbors nearest to king are names of specific rulers and kingdoms. Pasenadi was the ruler of the kingdom of Kosala, Ajātasattu the king of rival kingdom Magadha. A mythological sovereign is mentioned as well: Sakka is the ruler of one of the heavenly realms in Buddhist cosmology, populated by celestial beings known as devas.

king -> kosala, pasenadi, yama, minister, ajatasattu, deva, magadha, sakka

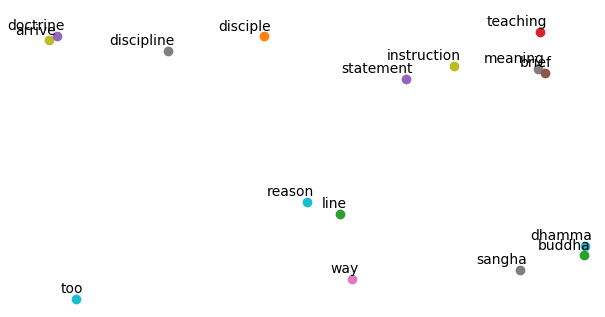

Buddha, Dhamma (or Dharma in other Buddhist traditions) and Sangha are the Three Refuges in Buddhism. Buddha refers to the historical Gautama Buddha (as well as other Buddhas referenced in various texts and traditions), Dhamma is a difficult-to-translate term that covers both the teachings of the Buddha as well as an overall system of cosmic truth and order, and Sangha is the monastic community. As expected, these terms are very close to each other in vector space, and each has nearest neighbors that are conceptually related. Several words refer to learning and teaching, and the Vinaya, the code of conduct for monks and nuns, appears with two.

dhamma -> sangha, teaching, buddha, meaning, goal, taught, statement, confidence

buddha -> sangha, vinaya, taught, well-taught, well-expounded, study, brief, rama

sangha -> buddha, well-taught, taught, well-expounded, recollect, approving, dhamma, vinaya

The t-SNE plot reveals them in close proximity:

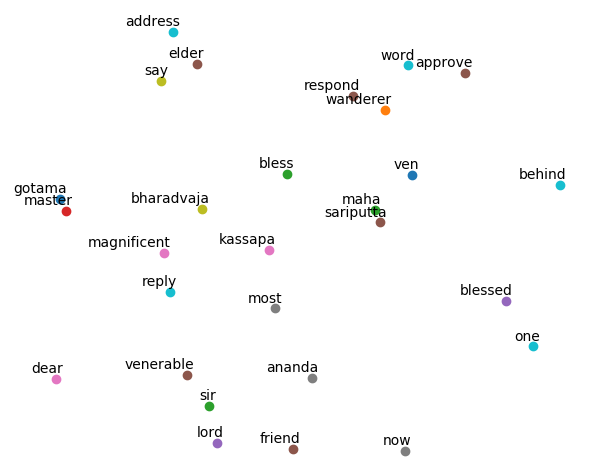

Gotama is the Pāli spelling for Gautama found in the suttas; Ananda was his cousin, disciple, and personal attendant. Ananda was reputed to have performed prodigious feats of memorization and was the initial oral chronicler of the Buddha’s teachings. He is mentioned by name more than any other disciple in the text by a significant margin and his name is a close vector to gotama. Also near gotama are several honorifics frequently applied in conversation with him, and near both are the names of other important disciples, including Sariputta, Moggallāna, Kaccāna and Raṭṭhapāla.

gotama -> master, magnificent, sir, bharadvaja, u, ratthapala, kaccana, ananda

ananda -> sariputta, samiddhi, udayin, maha, cunda, headman, kaccana, moggallana

These figures are all positioned closely on the t-SNE plot, which also includes maha and kassapa, referring to Mahākassapa, a key follower who assumed leadership after the Buddha’s death.

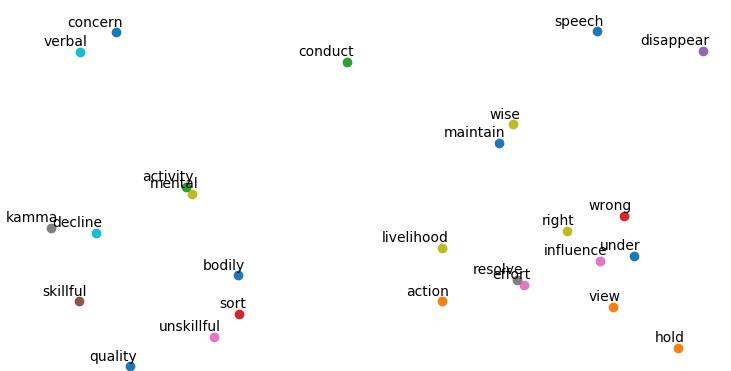

I also evaluated words related to the Eightfold Path. The Eightfold Path includes right view, right resolve, right speech, right conduct, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness and right concentration. Suttas often include opposing terms (like wrong view) when contrasting behaviors that are and are not representative of these qualities. Below, the vectors for elements of the Path strongly relate them to descriptive terms used for each. In particular, speech is near words for different kinds of wrong speech (divisive, chatter, false, abusive and idle), and mindfulness is near words that are used frequently when describing mindfulness and meditation (in-and-out, breathing, concentration, effort, and persistence).

eightfold -> path, forerunner, precisely, considers, namely, cultivate, undertook, non-emptiness

right -> undertook, wrong, livelihood, resolve, effort, disappointed, under, eightfold

wrong -> livelihood, undertook, influence, resolve, right, lowly, view, art

view -> undertook, wrong, resolve, doctrine, eightfold, hold, influence, path

resolve -> livelihood, undertook, influence, effort, wrong, action, view, memory

speech -> divisive, chatter, false, abusive, livelihood, misconduct, influence, idle

action -> resolve, undertook, livelihood, influence, consequence, verbal, deed, course

livelihood -> undertook, wrong, resolve, lowly, influence, art, effort, speech

effort -> livelihood, resolve, undertook, diligence, influence, endeavor, strive, alertness

mindfulness -> in-and-out, breathing, concentration, cultivate, effort, immerse, persistence, livelihood

Most of these are positioned together by t-SNE as well, although some have other stronger associations with concepts and terms beyond the Eightfold Path, resulting in them appearing elsewhere.

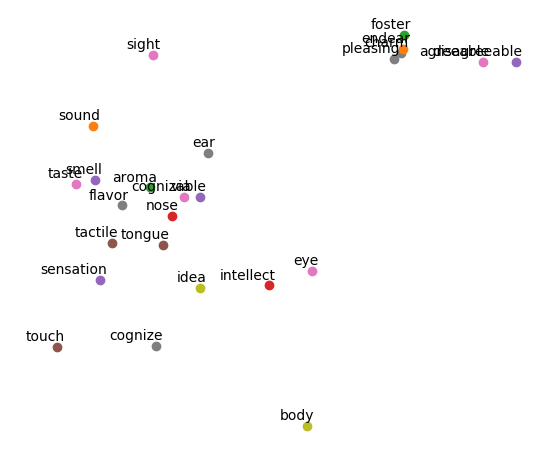

One of the most obvious concentrations of word associations in the results is the one for sensory terms. This includes the names of sense organs, senses themselves, and properties of objects related to the sensory experience. The phrase cognizable via is commonly used when describing senses and makes an appearance in the associations as well.

eye -> intellect, nose, ear, ear-element, form, tongue, unsuitable, sound

ear -> nose, aromas, aroma, tongue, via, flavor, soggy, cognizable

smell -> aroma, odor, taste, flavor, nose, tactile, via, sensation

sound -> flavor, smell, cognizable, nose, taste, aroma, aromas, via

sensation -> tactile, tongue, flavor, nose, taste, via, cognizable, odor

They are almost stacked on top of each other in the t-SNE plot:

Conclusion

I’m pleased with the results of this project. After some research, I was able to generate high-quality word embeddings on a uniquely special-purpose data set that, to my knowledge, has not been the subject for machine learning analysis before. I believe the following might help even further improve the quality and usefulness of results:

- Using a larger subset of the Pāli Canon, from a single source or translator. As mentioned, the text included in the corpus here is at best 40-50% of the total Sutta Pitaka alone, and the various translators often use significantly different vocabulary.

- Applying more nuanced and finely-tuned preprocessing that handles non-English words, an unusually high amount of repetition and elisions. For example, SyntaxNet might improve POS tagging and stemming performance.

- Employing techniques from a more advanced word embedding model like GloVe, which is specifically focused on spatial relationships and can perform better than word2vec on analogies.

I continue to be impressed by how easy it is to build and iterate on powerful machine learning models in Tensorflow. The embeddings generated here, while interesting enough on their own, will be useful as features for subsequent work, which I’ll continue in a future post.

You can find the code for this post on Github.